|

|

|

|

|

|

Travels with Devdas: Notes on Image-Essay

Travels with Devdas

Click on the images to blow-up

Travels with Devdas: Notes on Image-Essay

Madhuja Mukherjee

This is an attempt to explain certain complex points taken up in my image-essay titled ‘Travels with Devdas’. Briefly, I have tried to highlight the fabrication of visual language and signs within popular cinemas, and ways in which such images constitute our memories and modes of story telling. I try to locate the historical trajectories of cinema and visual cultures, as well as the manner in which images travel in cinema. The method is not discursive, but analytical. I take P. C. Barua’s film Devdas (Hindi, 1935) as a point of departure and elaborate how his narrative style influenced a cinematic idiom that, grows through other ‘Devdases’. For instance, writing about Devdas (1935) K. A. Abbas wrote in Film India, June 1940, -

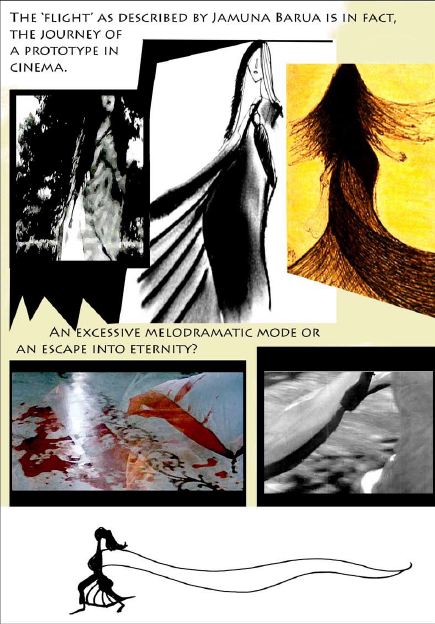

Do you remember it? Out of the very lens of the camera walked away the slender figure of a woman, going further and further, her back turned to the audience, a puja thali in her hand. A beautiful figure-and mysterious. The audience kept guessing; who is she and why? And where is she going? ….

The use of the Pujarini (worshipper) image becomes a crucial element as we discuss the ways

in which Devdas initiated a range of visual possibilities. When Barua borrowed the plot from Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s 1917 novella (in Bengali) it addressed an audience, which was familiar with the popular characters and situations. However, the film created its own range of meanings, and one of the most enduring characters in the history of Indian popular cinemas. The meaning of ‘Devdas’ is not contained in one film. Moreover, Devdas has been made and remade in several Indian languages. The most significant versions (in Hindi) are Bimal Roy’s 1955 film, and more recently its operatic remake by Sanjay leela Bhansali in 2002, along with its post-modern retake in Dev. D by Anurag Kashyap in 2009.

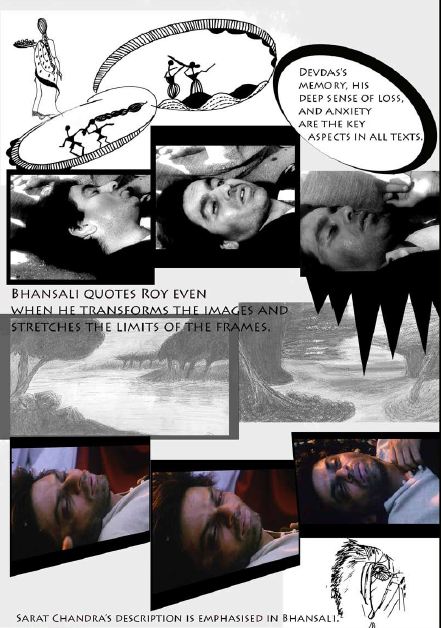

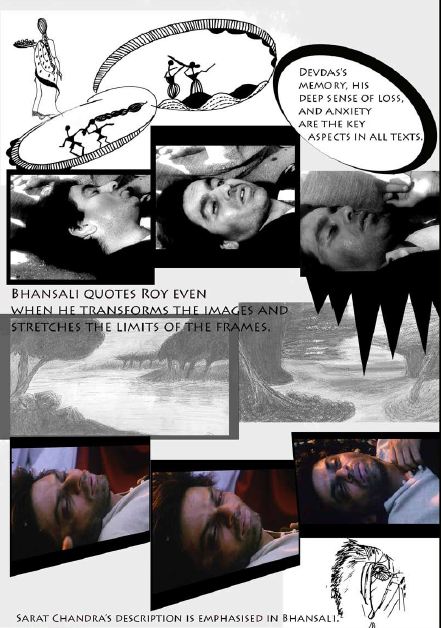

The first two ‘Devdases’ not only borrowed the ‘plot’ from Sarat Chandra’s novella, but also adapted ‘narrative’ elements from Barua’s Devdas, especially for the last scene1. For instance, Sarat Chandra illustrates in pictorial detail the end of the dying Devdas, and the state of the dead body in almost wearisome details. Evidently, Bhasali emphasises such fine points. Sarat Chandra writes2, -

Devdas wanted to raise his arms, but he couldn’t; two teardrops rolled down his cheeks. The coachman had the presence of mind to lay a makeshift bed of hay on the stone platform that ran around the peepul tree ….

Here, Parvati is cut down to a inert image, as she gets to know about of Devdas’s death. Interestingly, in the film

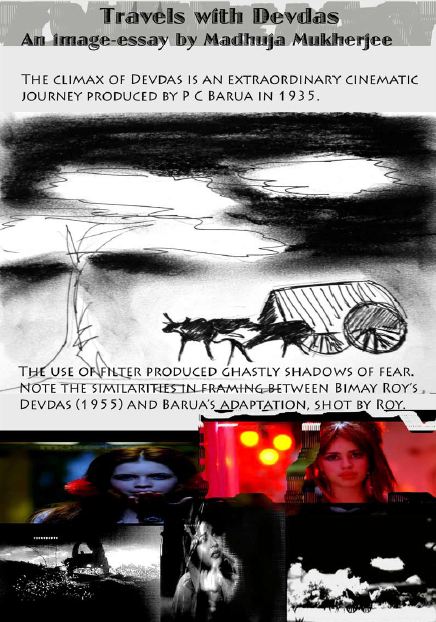

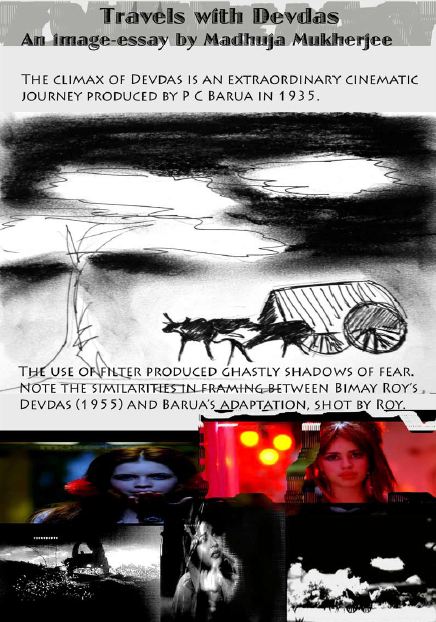

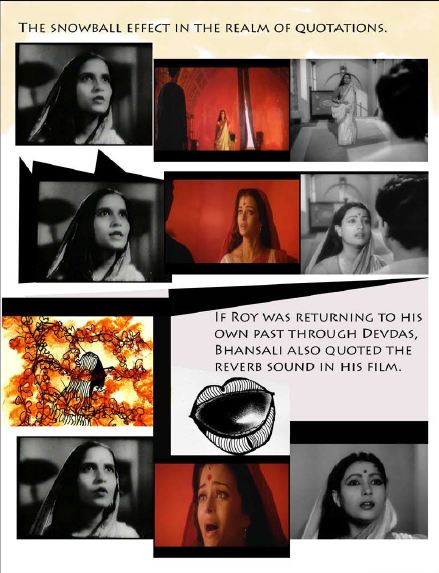

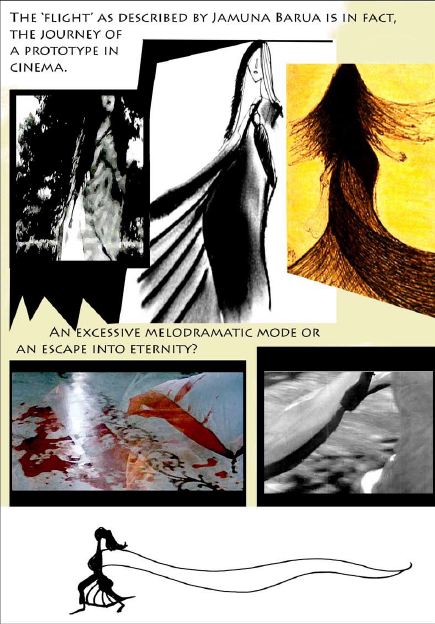

the sky turns black and leaves turn white as Devdas gets closer to Parvati and death. Barua had used a certain kind of coloured filter to get this dark and sinister ‘wash’ effect. In fact, in the elaborate last sequence the door becomes a symbol of Parvati’s entrapment as Barua inter-cuts shots of Parvati running through the vast structure (towards dying Devdas), with the shots of the enormous door slowly confining her3. The last shot of the film, the burning pyre, and K.C. Dey singing the timeless song ‘Teri maut…’ (‘Your Death….’) became a visual style for later films. The funeral pyre becomes a signifier of the futility of life and struggle. However, there is an apparent celebration of romantic love that attains fulfilment through death. Contrarily, the novella ends with the narrator trying to arouse pity for the tormented soul. Reacting to this comment, Jamuna Barua in an (personally recorded) interview hinted at Sarat Chandra saying, “I could not do what you [Barua] have done….” Publicized as ‘Devdas is a story of broken hearts’ the film demonstrates an effort to visually transform Sarat Chandra well known (realistic) narrative style. Pages 03 and 04 of the image-essay describe these points.

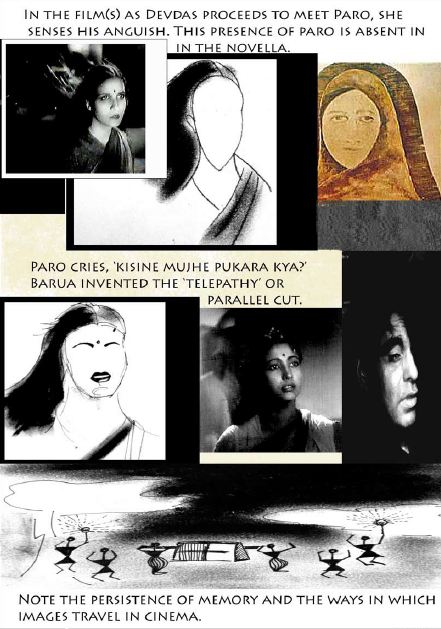

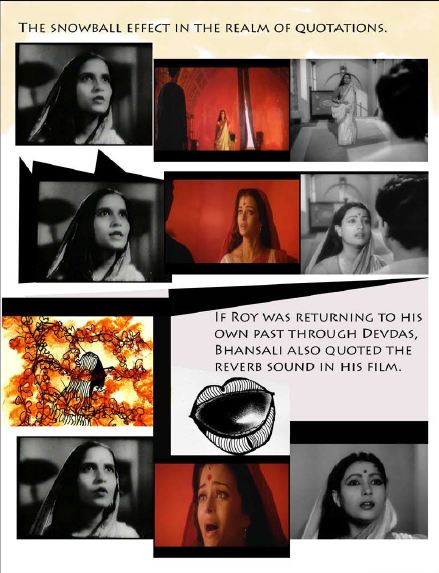

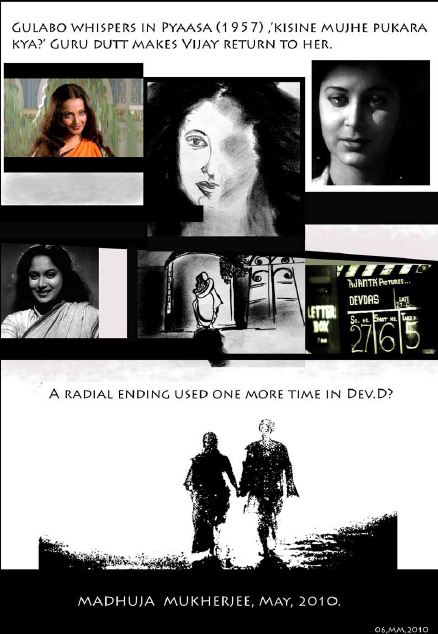

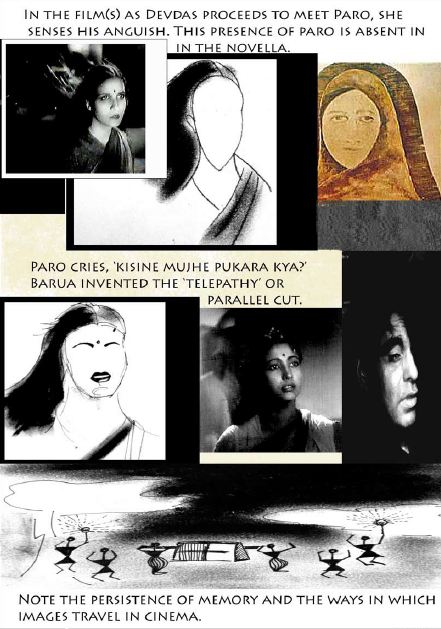

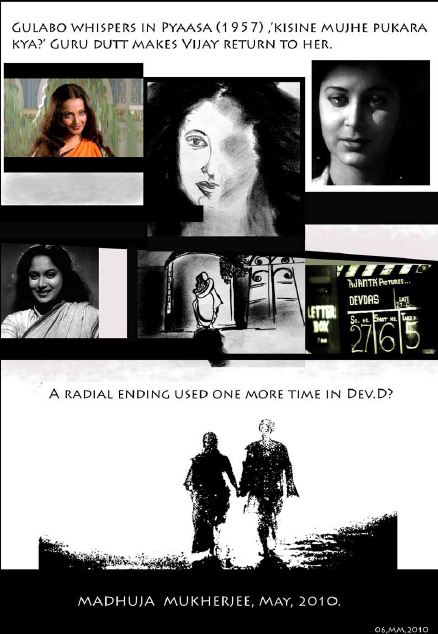

However, the shifts from the novella to the film are not merely in the modes of depiction. In his attempt to construct a film language and sensibility, Barua shifts from the past tense-the common mode of address in literature- to the present, to the here and now quality of cinema. Thus Barua’s interpretations are not merely images of a(prior) verbal description; in the process, he also comments on the two modes of expressions, just as he invents images to portray the experience of grief, pain, loss and death. Barua’s contribution to Indian popular cinemas is his ability to invent new vocabularies as he locates the implications of exchange. For instance, the long sequence in the film where Devdas is struggling for life inside a train is juxtaposed with Parvati imagining that someone is calling out to her. She wakes up from sleep and somewhat unknowingly runs towards a window. A rather jerky track follows her movement. This is followed by the enigmatic image of Parvati looking out to nowhere (to be used later in both Roy’s and Bhansali’s film). Parvati’s expression, ‘Kisene mujhe pukara kya?’ (or ‘Did someone call out for me ?’) is as a matter of fact, used in Guru Dutt’s Pyaasa (Hindi, 1957) as well. This persistence of a singular image outside the literary text, and the deployment of parallel cutting (described as ‘telepathy cut’ in popular journals) have crucial cinematic functions. Page 02 of the image-essay illustrates this. In fact, Guru Dutt not only quoted Devdas in Pyaasa (1957) he introduced a radical ending by forcing Vijay (or contemporary Devdas) to return to Gulabo (Chandramukhi?), the sex-worker. The question of love becomes complicated in Pyaasa, as Gulabo represents a rather complex love affair with city and work.

Guru Dutt’s obsession with the Devdas figure becomes apparent in Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959).Certainly the protagonist is making ‘Devdas’ within the film (and finds his Paro, who eventually becomes a public woman of sorts), and later as a failed director becomes a recluse and alcoholic. More importantly Dutt also shows the sense of alienation within emergent modernity. He complicates the plot by narrating the history of the studios (especially that of New Theatres Ltd.) and referring to films like Vidyapati (1938), Street Singer (1938) or Nartaki (1940), he highlights the disintegration of the benevolent studio structure, and the rise of super stardom in the war condition. Even the present-day the self-hating urban hero -Vijay once again - in Muqaddar Ka Sikandar (Prakash Mehra, 1978), has been read as a Devdas-text. The film transformed the early 20th Century Bengali Bhadralok into the post-colonial, post-emergency angst ridden angry young man, who has been betrayed by his beloved.

Moreover, a recent film Missed call (Toolsidass and Subramanian, 2003) has also been read as a critical expression of Devdas, since the anxious protagonist moves from his beloved to a call-girl, though his anguish grows primarily from his desire to be a filmmaker. Devdas becomes the urban folklore of our times primarily because of the ‘obsession with Paro’ and the death-wish, which in fact, may be replaced with other predicaments. For instance, it may be read as the tensions between city and village or self and cinema. And, this holds true for Barua as well.

To illustrate the ways in which the Devdas images travelled in cinema it is important to explain the ways in which P. C. Barua understood image-making. Barua wrote in Varieties Weekly (January 1934, Varieties Annual)-

There is a marked gesture in Bengal’s filmdom which shows a leaning towards the production of stagy and melodramatic pictures and it is interesting to try to analyse the reason for this inclination….

Certainly, Barua was seeking a language that was distinct from both stage and literature. And, in 1943 (Roopmanch, Bengali, March 1943) he wrote4 -

[t]he camera is the eye of the director… s/he can reach ‘imagined spaces’ [‘kalpanar rajya’: imagined nation?] through camera. Otherwise, his [/her] vision-creation-emotion and the film will be blurred.Barua’s rather well-known, innovative and somewhat ambitious track shots in Devdas and Mukti (1937) bear out his thoughts. Nevertheless, the study of Devdas has always been marked by the lure of hagiographical tendencies. Historians like Ashis Nandy (2001) draw parallel between P.C. Barua’s life and the Devdas figure, who like the melancholic-alcoholic hero, suffering from anxiety and TB had drifted from the ‘original’ space to the city seeking education, work and perhaps also destruction and death5. In effect, for the audiences in the 1930s and later, Barua and Devdas were practically identical. Barua, himself remarked in 1951 (as quoted in Ramachandran, 1985, 50)6-

Devdas was in me even before I was born, I created it every moment of my life much before I put it on screen and yet, once it was on the screen, it was more than a mirage, a play of light and shade and sadder still, it ceased to exist after two hours.Nevertheless, that “virtually a generation wept over Devdas” (Barnouw & Krishnaswamy, 1980, 80) is crucial7. In fact, it’s rather peculiar that the singing ‘star’ of the film K. L. Saigal8, also suffered from Devdas’s alcoholism, and died at the age of forty two; while the author Sarat Chandra, who had travelled from the village to the city, himself was an alcoholic and is also remembered for his irrepressible life-style. Perhaps it is kind of uncanny that so many biographies merge into this one narrative and character, raising serious questions about the apprehensions regarding modernity, that produced nearly ‘pathological’ recognition with the film and the character. Eric Barnouw and S. Krishnaswamy (1980, 81) wrote-

[t]o some extent Devdas was a film of social protest…undoubtedly gave some satisfaction…to those who hate this institution….Doom itself has appeared to become irresistibly attractive.

Indeed, ‘drinking’ seems to acquire a metaphorical meaning and to quote Elsaesser (1987, 65)9-

characters are seen swallowing and gulping their drinks as if they were swallowing their humiliations along with their pride, vitality and the life-force ….The visual rhetoric produced through Devdas (1935) creates its own spectrum of meanings, which are outside the novella. Moreover, what is exciting is the manner in which technology is addressed, as Barua’s adaptation of the novella confers to such self-conscious efforts. As Barua made films he did not simply borrow a plot; he also produced a visual discourse by situating Devdas within new possibilities. The attempt here is to explore the meaning and the significance of these new images within the emergent film form, language and film sense. To quote Ritwik Ghatak from Filmfare (July 1966)-

Here was a man who, in the late thirties, sometimes explored the potentialities of this plastic medium….he utilized the subjective camera to telling effect….Though, in the ultimate analysis he remained a product of his milieu.It may also be suggested that, Devdas becomes fascinating for the ways in which it shaped cinematic vocabularies. For instance, it popularized at least three significant images that dominated Indian cinemas for quite some time.

The figure of the condemned lover who eventually, takes to drinking and suffers from Tuberculosis; The ‘filmi-baiji’ (courtesan) who is a remarkable performer, a mysterious ‘public’ woman, who is ‘chaste at heart’ and remains ‘virginal’ despite her social positioning; And, perhaps more consequentially for the cinematic language the visual code of the train, cutting across unexplored expanses of rural India that remain in our memories as one of the most exciting visual design. The purpose of this image-essay is to depict the formation as well as the representations of such complex visual practices. Most certainly, Devdas is not the love story of a rich boy and a poor girl, ‘Devdas’ the film and character, are symbols of its times. It represents the historical-political trajectory of the nation. Devdas projects the anxiety of early 20th Century and later, and becomes a symbol of the historical events. The popularity of Devdas is perhaps rooted in the fatal uncertainty, as the nation was caught on the changing tracks experiencing the ruthlessness of political, economic and cultural colonisation, as well as transformations which is perhaps visually described through the ‘train-journey’. A journey, which is a process, which possibly leads to the realization, acceptance, and the Denouement.

Indeed, ‘Devdas’ is an enduring image that is beyond the film. Devdas is a mythical archetype that meant many things to many people. For B.N. Sircar the proprietor of New Theatres Ltd., it meant adaptation of a literary text, for Barua, Saigal, and Sarat Chandra it represented their own narratives, and for many of us it is a signifier of an entire generation and the most powerful allegory of Indian cinema. KA Abbas (Film India, June 1940) wrote that Barua’s films were,

always popular with the intellectuals (not necessarily progressives) because they are reflection of their own minds, sentimental, pessimistic, confused, and constantly groping towards reality. Escapism [Mukti?] – the urge to run away from the unpalatable realities of life – has characterized all Barua pictures. Devdas tried to run away from himself by wandering all over India, the artist in “Mukti” sought peace, a la Gauguin, by taking refuge in jungle….

Indeed, Mukti is a reverse Devdas, where the rural gentry do not come to the city; instead the city-bred artist escapes his own milieu and goes to the jungles - of Assam - to eventually die. The outdoor location shots of Mukti (with the sweeping pans moving over trees, bushes, shrubs, while the vast dominating sky looms large over the greenery which is placed towards the bottom of the frame) have been described as being influenced by the Bengal School paintings. Moreover, the use of diffused light (or ‘wash-technique’ in cinema) along with the famous Rabindra-sangeet ‘Diner sheshe ghumer deshe…’ (scored by Pankaj Mullick), is a momentous cinematic gesture. The Bengal School was in a self-conscious way influenced by Japanese art where elongated frames have empty upper halves, while figures are placed at the lower half of the frame. The presence of nature and sky are the defining factors of Japanese painting. The void creates an uncanny sense of emptiness and perhaps a sense futility, which is a dominant philosophy of many post-war Japanese films. Moreover, the method of application of (water) colour and the ‘washing’ away of it was new within the Indian context, since the common practice was to smear solid or thick coats to produce a jewel-like effect. The unique wash-technique produced an unusual (diffused) light quality that Barua seems to have borrowed in his films. However, in my opinion Barua appears to have an over-all ‘Rabindrik’ (‘Tagorean’) influence as it were, in the manner he uses the mystifying slender figure and face of Jamuna Barua. Besides Rabindranath Tagore’s own involvement with Mukti, the darkness and the geometric structures of the interiors in Barua’s films (as in Adhikar, 1938) may remind one of some of the paintings of Gaganendranath Tagore. As a matter of fact, the uses of light in the interior spaces are somewhat dramatic and expressionistic and are remarkably different from the wash technique. By using my own illustrations and found images I have tried to highlight these diverse trajectories in the image-essay, emphasizing how a cinematic style is formed and the processes through which cinema quotes its own of visual histories10.Notes

1In the article ‘Devdas, 2002: Adapting the Devdas myth’, 2003, in Susanta Mukhopadhyay (ed), Indian Film Review, Delhi/Kolkata, I have tried to explain how the film borrows from multiple sources and discuss the question of inter-textuality in popular cinemas.

2From the 2002 Edition, translated by Sreejata Guha, a Penguin Books Publication, New Delhi.

3“He was showing that the society always shuts the door for the women…” said Jamuna Barua in a personally recorded interview.

4See Rudra, Subrata, 2004, Pramathesh Baruar Jiboncharit (Bengali), Aruna Prakashani, Calcutta, 103.

5‘Invitation to an Antique Death: The Journey of Pramathesh Barua as the Origin of the Terribly Effeminate, Maudlin, Self-Destructive Heroes of Indian Cinema’ in Dwyer & Pinney (ed.s), Pleasure and the Nation: The History, Politics, and Consumption of Public Culture in India, OUP, New Delhi.

6 Ramachandran, T. M. (ed.), 1985, Seventy Years of Indian Cinema, 1913-1983, Cinema India International, Bombay.

7 Barnouw, Eric & Krishnaswamy S., 1980, Indian Film (2nd Ed.), OUP, New Delhi.

8In 1946, at age of forty-two, Saigal died of alcoholism somewhat like Devdas. Surely, this was a perfect situation for his admires to consider this death as a wonderful merging with the Devdas myth. Apparently, after his death, the radio stations throughout the nation played his poignant songs from Devdas (and many other films as well) for several days, while the instance seemed like bemoaning for a ‘hero’ in every sense of the term.

9‘Tales of Sound and Fury: Observations on the Family Melodrama’, in Gledhill, Christine (ed.), 1987, Home is Where the Heart is: Studies in Melodrama and the Women’s Film. BFI Publishing, London.

10This is a reworked version from my chapter on the cinematic journey of Devdas, through ‘texts and contexts’, in the book New Theatres Ltd., The Emblem of Art, The Picture of Success, 2009, published by NFAI, Pune.