POETRY Magazine - A Reminiscence

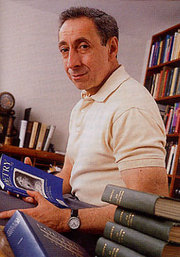

An interview with Joseph Parisi (2007)

Ankur Saha

Joseph Parisi (b. 1944) was Editor-in-Chief of POETRY magazine from 1983 to 2003. His most recent books are 100 Essential Modern Poems (2005) and Between the Lines: A History of POETRY in Letters, 1962-2002.  He was born in Duluth, MN, and grew up there, and in Northern Wisconsin and Upper Michigan. Parisi went first to public then to parochial schools, including a Catholic high school. He received his B.A. at the College (now University) of St. Thomas, St. Paul, MN, (1966), M.A. (1967) and Ph.D. (1973), with honors, at the University of Chicago. His field was 18th-century English literature, particularly drama.

He was born in Duluth, MN, and grew up there, and in Northern Wisconsin and Upper Michigan. Parisi went first to public then to parochial schools, including a Catholic high school. He received his B.A. at the College (now University) of St. Thomas, St. Paul, MN, (1966), M.A. (1967) and Ph.D. (1973), with honors, at the University of Chicago. His field was 18th-century English literature, particularly drama.

AS: When was your first encounter with the Poetry magazine? When did you see the first issue? What was the impact on you ?

JP: I heard about the magazine when I was in college, but don’t remember seeing a copy until I went to Chicago. I wasn’t particularly interested in contemporary poetry in my college or grad schools days, and actually spent most of my time in the Music department in college, playing in the band, accompanying soloists, singing in the choir, etc.

AS: Who was the editor at the time you joined POETRY ??

JP: I joined POETRY as Associate Editor in 1976, at the request of then-editor Daryl Hine, who had earlier asked me to do some book reviews for the magazine. I worked part-time for the first few months, but soon was asked to come on full-time.

I started as the first reader of manuscripts and production manager. I was also proof-reader, and did standard editorial work. Then gradually I took on other jobs, particularly in publicity and public programming. I later started to help with fund-raising, which I tried to make more systematic. During my first 11 years at the magazine, I was also teaching full time. (Salaries were not large at the magazine, and without the other job teaching, it would have been hard for me to get by.)

AS: . You are not a poet by nature or profession. What made you gravitate towards POETRY magazine? What made you successful? Is there another example of a non-poet successfully editing a premiere poetry magazine for two decades ?

JP: I didn’t “gravitate.” As I said, I was invited. I said I’d give it a try and see if it worked out. I would not have thought of applying for a job there.

Why successful: primarily lots of hard work, and a willingness to try new things, esp. public programs, to increase awareness of the magazine and appreciate of poetry.

As editor I had one great advantage: as a non-poet, I was never tempted to play the po-biz games many editors in the field have played, and still do: printing certain people so that those certain people would in turn print them. I was never in the business for advancement of my own career. I didn’t have personal ambitions in poetry, which gave me a certain moral leverage: I chose poems and tried to help people, esp. young writers starting out, based solely on the quality of their work. I think people appreciate that fact.

Other examples? None that I know of. But Peter De Vries was an editor at POETRY for many years, including editor in chief during World War II. And he was very successful one, keeping the magazine going in the very hard economic times during the war, and after. De Vries was always primarily a novelist, though he printed a few poems in his younger years. He eventually joined The New Yorker and spent the rest of his career there mostly writing short humorous pieces and handling the cartoons.

AS: Magazines that deal with poetry seem to do well for a while and then die for no apparent reason. What is the secret of the longevity of POETRY ?

JP:There are at least two or three very good reasons why most little magazines die: it’s a lot of work putting out a magazine and (young) people get tired trying to keep it going; or they lose interest, seeing how boring most of the work is. But mainly little poetry magazines fold for lack of money.

POETRY’s “secret” was generations of editors who worked for little or no wages, and many readers and other supporters who subscribed and gave to keep it going. Even so, the magazine came near to bankruptcy and to closure at least 5 or 6 times over the years.

Because of its famous early “discoveries” (T. S. Eliot, Wallace Stevens, H.D., etc., etc.) established a strong reputation early, which made it a—some say THE—place young people wanted to appear ever afterward. It was the magazine’s traditional emphasis on quality that was most important to would-be contributors. Also, it’s reviewing was extensive and fair: lots of readers looked at the magazine maybe primarily for the criticism.

Further, the editors were personally very kind to people, and always polite to everybody. Harriet Monroe started that tradition of personal contact and concern, and her successors tried to emulate her, even though it became increasingly difficult to do, given the small size of the staff and the growing numbers of people writing and submitting over the years.

AS: How was a poem selected for POETRY? Can you please walk us through the process after a manuscript comes in? Were there written guidelines for selection or is it more of a personal; preference.

JP: In my time, there was usually only one, occasionally two first-readers. I saw about 1/4 to 1/3 of the pieces that came in, after they sifted the manuscripts. I read all of the poems that reached my desk, every night and usually weekends, too, and replied personally to most of the authors that were passed on.

There was only one person making the final decisions: me. There were no written guidelines. But we didn’t play favorites or chose poems just because the author happened to be famous. In fact, the hardest part was sending poems back to very well-known authors, which I quite frequently did. About one-third of the authors I published each year were first appearances.

AS: How many manuscripts did you get on average in an year? How many did you select? Do you respond to every poet? How many people did you have on your staff?

JP: In the beginning of my time, in the seventies, perhaps 50,000 poems came in annually. By the end of my tenure, maybe 80,000 or more. From these we could take between 300 and 350 per year, on average.

The staff during my editorship consisted of myself, an associate editor, one part-time or full-time assistant editor, and a business manager. There was also a subscription manager who helped with clerical and accounting jobs, and sometimes some editorial tasks. But generally the staff was the editor plus 4 to 5 others, with a few part-timers and volunteers in busy seasons (e.g., to help with preparations for Poetry Day readings, the annual fund-raiser).

AS: How many were from outside North America? Did you get significant amount of poems in English from third-world countries? Any particular country that caught your attention?

JP:

We got submissions from all over the worlds, esp. from Great Britain, Ireland, and India and Pakistan; but also the Commonwealth countries, S. Africa etc.

AS: In 1977, you edited the first POETRY Anthology with Daryl Hine. How did it get started? What was your experience in selecting poems for the Anthology? Was it intimidating?

JP: The anthology was proposed, well before I joined the staff, as a possible way to make money: an absurd idea. It was a tremendous amount of work: we went through every single issue, starting from 1912. The text of the anthology was very large to begin with, but had to be cut down three times, at the request of the publisher. As a result, we had to delete several poems (and authors) we felt were important in the history of the magazine, which did not please us, or the authors who found themselves excluded.

I said I would never do another. But of course I did eventually: The POETRY Anthology 1912-2002 covered even more years and thus thousands more poems had to be reviewed; the book was put together to help celebrate the 90th Anniversary. Stephen Young, co-editor of that anthology, also helped in the preparation of Dear Editor: A History of POETRY in Letters, 1912-1962, which also came out in 2002. We thus had twice the work to do. That volume was based on the correspondence files of the magazine; we read through well over 300,000 documents to prepare the history of just the first fifty years, then another 300,000 or so for the last four decades.

AS:What is your impression of Daryl Hine, as a person, poet and editor?

JP: Daryl was (and is) an extremely intelligent, widely read, and witty person. He is a scholar of Greek and Latin, and has published many translations from ancient Greek. He is also proficient in French. You should check on Amazon.doc for a list of his many books, both original volumes of poetry and translations.

It was he who invited me to join POETRY in 1976, and we worked very closely together at the magazine, though only for about a year and a half (he resigned in late 1977). We co-edited The POETRY Anthology 1912-1977, which was a large and delicate task. (I said I’d never do such a thing again, but as you see, I’ve now committed two further poetry anthologies, and am now completing still another one.) Our time together was mostly pleasant, perhaps because we share the same sense of humor, and many similar interests, though not entirely the same tastes in poetry.

Daryl’s time at the magazine had its ups and downs, good days mainly in the early years, but less pleasant ones by the mid-point and later. Temperamentally he was not the sort of person to enjoy doing promotion, publicity, or fund-raising, which became more important as the 70s wore on. Further, he found the tasks, editorial and extra-editorial, more and more a distraction from his own work, as I say in Between the Lines. I think he was extremely pleased when he left the editor’s chair with its endless irritations large and small, and returned to do his own writing exclusively.

AS: You included many non-poets (traditionally) in the Anthology, like James Joyce, Margaret Mead, Gertrude Stein and so on. Was there any particular reason?

JP: James Joyce was a poet. Gertrude Stein considered herself one, as well. A few authors printed in POETRY early in their lives and eventually famous in other fields were included because their poems happened to be good. We included them in part to show how wide the range of contributing authors was over the years.

AS: How did Poetry change from one editor to another. did you make alterations in the running of the magazine when you took over the helm from John Frederick Nims?

JP: To answer that question, I would refer you to the two histories of the magazine: Dear Editor and Between the Lines, in which I give very detailed analyses of the differences between editors, and their literary eras, the historical/literary backgrounds, and so on. Again, people should just look at some of JFN’s issues and then look at ones I edited, and draw their own conclusions from the comparison.

I will only say that all my issues were organized as small integrated books, little anthologies with related themes and sub-themes or topics, not hodgepodges or mere miscellanies.

AS:. When did you receive the first poems from Mrs Guernsey van Ripper Jr ? Tell me about your reaction ? How did her relation with the magazine grow?

JP: I can’t remember, but sometime in 70s. I sent a short thank-you note. The relationship grew when she decided to award the Lilly Prize and her lawyer then asked me to help set it up. The lawyer at the time asked me to be the chief judge, which I was, as well as chief administrator, for its first 18 years. She then asked me to help set up what became the Lilly Poetry Fellowships. She also responded to various requests I submitted to underwrite special issues and other projects over the years.

AS: Does money help or hurt poetry?

JP: That’s for individual readers to decide.

AS: How was the relation of the Beat Poets with the Poetry magazine? Ginsberg had one poem published there in the 80's. Kerouac never wrote there. Was there any philosophical difference between the magazine and the Beat Generation? Was Poetry too formal or eclectic for them?

JP: Again, you can read about that in Dear Editor, in detail. I add further factual material on the subject also in Between the Lines. I tried to dispel several erroneous, often repeated comments about the Beats there. In fact, many of the Beats did appear in POETRY over the years. And their books were reviewed regularly. Check the general Index.

If they chose not to submit work to the magazine, that wasn’t the magazine’s fault. I’d say that such Beat poets as didn’t send pieces or appear there did not constitute a great loss. I’d also say that POETRY was far more open, and open-minded, and inclusive in its editorial policies than most of the Beats were.

AS: Tell us more about your interactions with John F Nims.

JP: John Frederick Nims was an extremely learned, multi-lingual poet and translator as well. Indeed, his greatest fame was and probably still is for his excellent rendering of poems in several languages. Also, he produced an excellent large poetry anthology (for Harper) and a textbook (Western Wind) widely used in colleges and universities across the country. His knowledge of poetry and poetics approached the encyclopedic.

John was very witty and a true gentleman (the two qualities don’t always go together). He spent enormous amounts of time writing short, individualized notes to authors whose submissions he returned. His rejection notes were usually far more interesting than the poems he was responding to. I think that some people didn’t really “get” his sense of humor or his sense of fun. He loved to play with words, and was a good raconteur. But I also believe he used his humor and linguistic skills to keep a certain distance from people. As far as his editorial work and decisions were concerned, he liked to play his cards close to his chest—probably a wise policy.

Nims did not care for promotion or fund-raising any more than Hine did, but he did do those jobs diligently and without complaint. His tenure was relatively short, but his years were particularly difficult because of money problems at the magazine, and it was not easy to keep the operation going in the late 70s and early 80s. At one point, he even took a pay cut so we could hold on. He certainly did not need the job, but took it because he felt a sense of duty to and concern for the magazine. He was also on the staff in the 1940s, and was later a visiting editor for a year, 1960-61.

AS: If you start a poetry magazine tomorrow, how different will it be from the magazine you edited for two decades?

JP: I would never do such a thing as start another poetry magazine. The one I edited for 20 years speaks for itself. Of course any new magazine would be different, since the people writing, the contexts, and thus the poems would obviously be different. How exactly? Who can say?

The interview was first published in Bengali script in Kabisammelan (October, 2007). English-printed here with permission from Shyamal Kanti Das, Editor, Kabisammelan.

-----X-----